A doctor’s deadly legacy

To go with a feature (by someone else) on the 9/11 ten year anniversary, I interviewed a doctor about her memories of the day.

To go with a feature (by someone else) on the 9/11 ten year anniversary, I interviewed a doctor about her memories of the day.

Published The Age, 10 September 2011.

Online here. After the break, the original, much longer piece.

By Nick Miller

New York

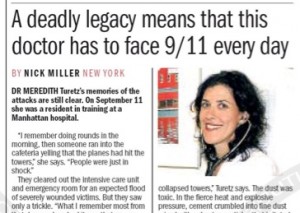

Dr Meredith Turetz’s memories of the 9/11 attacks are clear. And a decade later she is still treating the victims.

She was a resident in training at a Manhattan hospital.

“I remember very clearly that day, doing rounds in the morning, then someone ran into the cafeteria yelling that the planes had hit the towers,” she says.

“People were just in shock. When you looked out of the window of our cafeteria you could see the planes all the way downtown, from lower Manhattan, and the smoke coming up.”

They cleared out the intensive care unit and emergency room for an expected flood of severely wounded victims. But they saw only a trickle.

“What I remember most from that day was how bad it was that no-one came, because everyone died. So that was very sad.”

Dr Turetz didn’t lose a friend or family in the attack, but she was deeply affected by them, like many in the community.

She became a pulmonologist – a lung specialist – in 2006 and now works at the World Trade Center Environmental Health Center, based at the Bellevue Hospital on the east side of Manhattan.

They have nearly 6000 patients affected by the attack – stockbrokers, students, cleaners and others in the downtown community who helped in the clean-up.

The health problems began soon after.

“Early on no-one knew what to expect so we started looking for patterns,” Dr Turetz says. “There soon emerged a pattern of illness in people exposed to dust from the collapsed towers.”

The dust was toxic. Cement crumbed in fierce heat and pressure into fine dust mixed with asbestos particles that irritated and damaged lungs and stomachs.

“Some got an immediate, intense exposure when they were caught in the massive dust cloud of the towers collapsing,” Dr Turetz says. “Then people had ongoing exposure if they lived in the area, the dust settled in people’s apartments and workspaces, it got through the windows, and it was blown back into the air, re-suspended and people were exposed that way. Not to mention that there were fires that burnt for several months as a product of diesel fumes, jet fumes.”

“This has been in many ways new medical ground, both an environmental and medical disaster.”

The effects were severe and often permanent. Respiratory problems range from persistent coughs through to debilitating asthma, sinus or digestive problems. Their stomachs or chests burn with acidic fire that moves up their throats, making it hard to eat.

“I have several patients who have severe, intractable respiratory problems,” Dr Turetz says. Even after regular treatment over a long period of time they are stuck on medication and frequently hospitalised by acute attacks, left literally breathless by the tragedy.

“(These are) people who may in the past have been very active, playing sports, they ran marathons,” she says. “Now they can barely walk without being symptomatic.”

Mental health issues complicate the physical treatment.

The American Medical Association published new research this week documenting the lasting mental trauma caused by of the 9/11 attack. It found that more than a third of people directly put in danger by the attack on the towers and their collapse – those forced to flee the falling debris or who were actually injured – had since been diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

One in five experienced PTSD simply by witnessing the attack, seeing injured or dead victims or the gruesome aftermath. Another third developed PTSD when a close colleague died or was injured.

Another study from the New York City Fire Department found that by September last year, more than seven per cent of firefighters who participated in rescue or recovery at the WTC site were still suffering PTSD.

The mental health effects of the attack can magnify the physical effects, Dr Turetz says, making it harder to treat both.

First-time patients are still coming forward – several every week – to the centre. Some have just learnt of the program, or just realised their ill health may be linked to the attack, or have lost their private health insurance and need to throw themselves on the public system (which is now well funded, for WTC victims).

But there may be an even bigger legacy of the attack, yet to show itself.

In that ominous-but-clinical way doctors have, Dr Turetz describes the data on WTC-triggered cancer as “a work in progress right now”.

Dr Turetz says the tenth anniversary is bitter-sweet.

“For me, from a professional point of view it is amazing we are seeing new patients even though that exposure was ten years ago,” she says. “And also it is a tough time because the tenth anniversary resonates a lot with our patients. As important as it is to remember and to reflect, for a lot of the patients it is a very difficult time.”